At the moment, the left is dominating the debates on income inequality. But it doesn’t have to be this way. There are plenty of reasons for people on the centre-right to be concerned by widened income gaps – and plenty of things they can say on the subject. Here are just three.

The first reason that the centre-right might worry about inequality is very simple: the economy. A well-functioning economy is key to centre-right thinking; it’s the thing that has to work before all other plans can come to fruition. Yet there is growing evidence that big income gaps are bad for growth. Both the IMF and the OECD have issued heavyweight reports showing just that.

The links between inequality and weak growth are many. A very unequal society has a lot of people who are struggling and marginalised; they – and in particular their children – are unlikely to make the economic contribution they could in a more equal world. Even middle class families see wages stagnate and struggle to invest in their children’s education as they would like.

At the other end of the scale, large amounts of income flowing to the richest tend to result in asset bubbles and speculative investment. Just look at the GFC: as poor households saw their incomes falling behind because most of the growth was going to rich families, they borrowed to keep up and to buy houses – and that borrowing came of course from the rich, who needed a home for all that cash splashing around. When that situation became untenable, it all unwound, and voila: a major global recession.

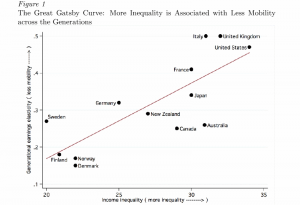

A second thing that might concern the centre-right is the effect inequality has on social mobility and equal opportunity. Social mobility – the idea that people should be able to do well, regardless of who their parents are – is another key centre-right value, and sometimes people insist it’s more important than income inequality per se. But there’s plenty of evidence that you can’t separate the two. The graph below, known as the Great Gatsby curve, shows that the very equal Scandinavian countries have ‘generational earnings elasticity’ of less than 20% – that is, less than 20% of your income as an adult can be predicted from what your parents earned. That’s pretty good: not perfect, but not bad either.

In very unequal countries like the US, however, fully half your income can be predicted from what your parents earned. That means that huge amounts of advantage are transmitted, and there’s nothing like a genuinely equal opportunity – a fair go, as it were.

It’s not hard to see the link, either. In very unequal countries, kids get very different starts in life, and that just compounds and compounds in later life. In equal countries, by contrast, most families have enough income to give their kids a good start in life, and free-to-all public services help close up any remaining gaps. Of course, as the graph shows, New Zealand is doing okay-ish at present. But we’d surely like to move closer to the Scandinavians – and the graph implies that we won’t be able to do so without first closing income gaps.

The third and final centre-right concern – and one that is fundamental to everything else – is around social cohesion. This is an idea dear to the hearts of what the British call One Nation Toryism, and what New Zealand commentator Colin James calls “small-c conservatives”. As he puts it, such people value order, since an orderly society “is likely to be safer and more congenial than a disorderly one”.

But a society in which there are large inequalities “is likely to become disorderly or at least less orderly”. We know from international evidence that as income gaps widen, people lose their understanding of and sympathy for the lives of people at the other end of the spectrum. Trust declines; volunteering to help others declines. That being so, “it would make small-c conservative sense to reduce those inequalities to the point where they do not threaten disorder.”

And that, James argues, points to the idea that we should think of a cohesive, well-functioning society “as economic infrastructure”. A well-functioning economy “requires investment in infrastructure: failure to build, restore and maintain roads or water or waste systems, for example, has an economic cost over time and investment in them a corresponding economic benefit over time. … If we accept that a cohesive, well-functioning society — one of unique individuals bound in common purpose — is also infrastructure, underlying and underpinning the superstructure of our material wellbeing and thus necessary to a well-functioning economy, we will invest in them, that is, build, restore and maintain them.”

The above arguments provide a solid foundation for a centre-right push towards greater equality. And where better to finish than with a quote from a former speechwriter to George W. Bush? Writing a few years ago, David Frum argued that equality in itself “never can or should be a conservative goal. But inequality taken to extremes can overwhelm conservative ideals of self-reliance, limited government and national unity. It can delegitimize commerce and business … Inequality, in short, is a conservative issue too.”

The post What does the centre-right have to say about inequality? appeared first on Inequality: A New Zealand Conversation.